11 Lavender & the strange tale of Monsieur Gattefosse

Posted on

That bee just wouldn't sit still.

Fougère, the French and the Aromatherapist

The fougère fragrances are a family of “man smells” which came into being at the end of the 19th century, all containing lavender. (Traditionally, anyway.) Fougère is French for fern, but ferns don’t really smell of much. What the fougère is, when you find it in a perfume bottle, is inspires by Houbigant’s original, imaginary version of what a fern ought to smell like.

As well as lavender, your fern fragrance will have bergamot, oak moss, and coumarin. The French think of lavender as of traditionally male fragrance, and use it in all manner of cleaning products too. The British dismiss it as a granny scent. Naturally this means that it’s due a comeback, like violets, roses, lily of the valley and honeysuckle.

Fougère fragrances have been around since the 1870s, and were only possible because William Perkin isolated coumarin in a chemical reaction in 1868. You also find it in tonka beans, but natural tonka costs an arm and a leg to extract. Yes, that’s right, every single fougère fragrance ever made for almost the last 150 years has been a mixture of naturals and synthetics.

Houbigant’s Fougère Royale, Penhalligon’s English Fern, and everyone else’s ferns have coumarin in them, thanks to a Victorian gentleman with a very large beard.

Lavender oil is also one of the leading lights in aromatherapy. The story goes that René Gattefossé, a chemist working with raw materials to create new synthetics in the late 1800s, burned himself in a laboratory accident. He plunged his hand into the nearest vat of liquid – lavender oil handily enough – and found that the pain went away quicker, and his hand healed far faster than he was expecting.

Knowing this, one day when I dropped a casserole straight out of the oven on to my bare feet, I doused myself in 100% undiluted lavender oil after running them under the cold tap. I wouldn’t go doing this with any old essential oil because I’ve seen their safety certificates, but in extreme circumstances lavender is the one you want.

I wouldn’t recommend that anyone puts this to the test, but after two days the scalds had stopped hurting and I didn’t get any scars. I was pleasantly surprised, and I’ve carried a bottle of lavender oil around with me ever since.

Mind you, up at the Vintage By The Sea festival last year, I met a chap who approached our perfume stall warily. He told us he had to be a bit careful with scent (and at this point he stood back a bit) because he is allergic to lavender.

He told me that he had mentioned this to an aromatherapist friend and she had scoffed at him, telling him that it’s impossible because lavender is calming. It is not impossible. People can react badly to lavender and I’ve now met two of them. It’s rare, but it happens.

Anyway back to René Gattefossé. He was so impressed by the effect lavender had on him that he stopped trying to isolate individual aroma chemicals and turned his research to what he called Aromatherapie (he was French) the medical use of plant oils. It was only in the 1970s that aromatherapy began to take on its modern, somewhat spiritual holistic aura, with the rise of the “back to nature” movement.

There was some recent research on lavender (I’ll try to find the source) to test whether or not the essential oil could calm people waiting for a dentist’s appointment. What happened was that they just started to associate lavender with feeling nervous. Any calming properties that it might have is entirely displaced by the new associations created by circumstances. (I think this is quite funny, but I do have an odd sense of humour.)

The point is that lavender is complicated. It does appear to do marvellous things to sore skin, burns and scar tissue. However no one is allowed to mention this on their product packaging or marketing materials because the compulsory 10 years of medical research hasn’t been carried out. It probably won’t be because no one wants to invest the money into it if they can’t patent it and keep all the financial benefits for themselves.

The scent of lavender is a complex mix of chemicals grown naturally. You can get lavenders grown at altitudes that smell different, some species which hardly smell at all, others which are grown entirely for their fragrant properties. It’s tangy and herbal on its own, rather than gentle and floral. There are synthetic lavenders too; never assume that your perfume contains a natural one.

Yardley’s English Lavender, by the way, used to be a fragrance for men. It swapped sexes somewhere in the middle of the 20th century.

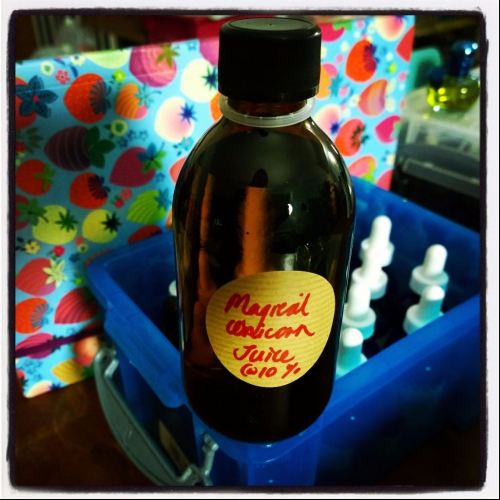

I use lavender in two of my most British fragrances, The Lion Cupboard and What I Did On My Holidays. The green tint in Holidays comes from lavender absolute which is a deep dark pine colour, a heart note. The lavender essential oil in The Lion Cupboard is much paler, a light topnote. I use the first as a reference to children’s suntan lotion and the second is a reminder of the traditional colognes and aftershaves that my dad very occasionally used.

I’m about to use it in something new.

On my way to work, I walk past lavender bushes in the Factory Quarter and front gardens along Valetta Road in Acton. That’s where the photograph comes from. They are always buzzing with bees. This leads me to another point. Whether or not you like the smell in your fragrances, whether or not you like to use the essential oil, if you have even the tiniest spare plot of earth in a plant pot or your garden, give it to a lavender plant. The bees need all the help we can give them.